James Webb Telescope Detects Potential Signs of Life on Distant Planet

A planet orbiting a distant star 120 light-years from Earth has shown the strongest signs yet of potential extraterrestrial life, according to new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope.

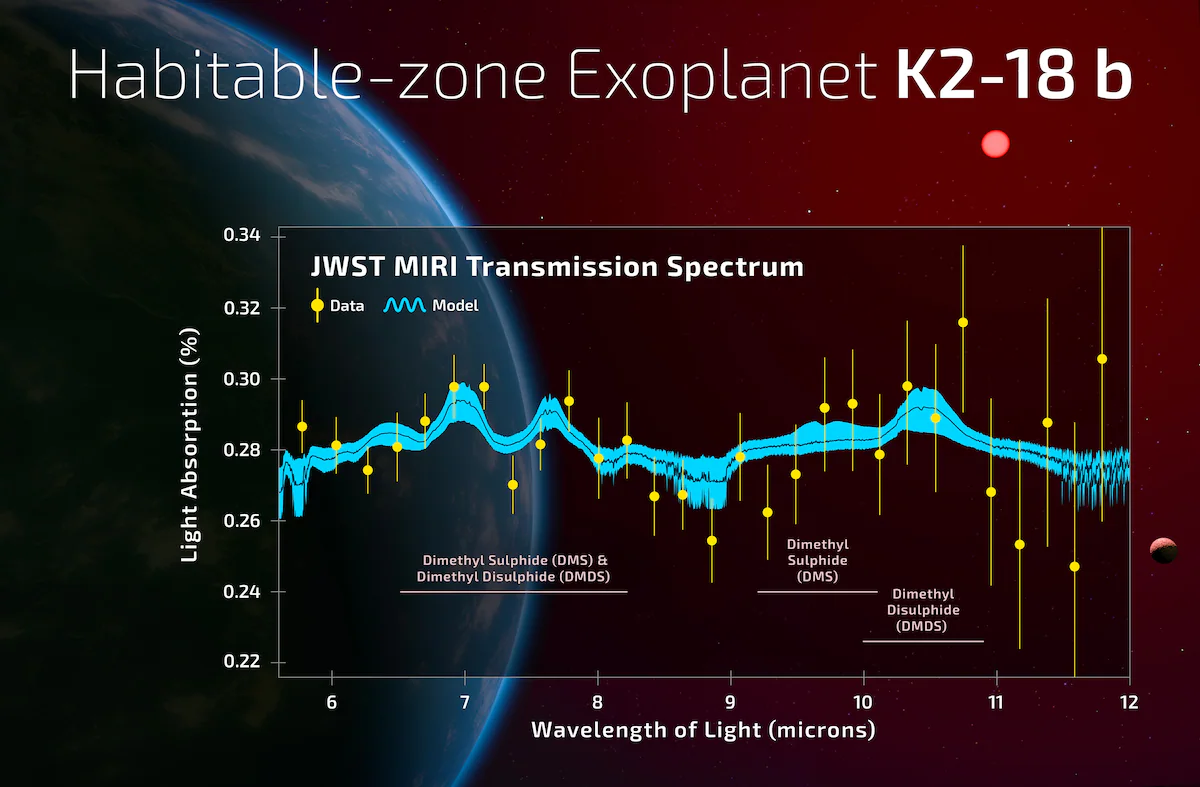

Astronomers have detected the chemical signatures of dimethyl sulfide (DMS) and dimethyl disulfide (DMDS) in the atmosphere of K2-18 b, a Neptune-sized planet located in the habitable zone of a red dwarf star in the constellation Leo. On Earth, both compounds are predominantly produced by marine organisms.

“This is the strongest evidence to date for biological activity beyond the solar system,” said Prof. Nikku Madhusudhan, an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge who led the research. “We are very cautious. We have to question whether the signal is real and what it means.”

The findings, published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, stop short of confirming alien life but bring scientists closer to answering one of humanity’s oldest questions: Are we alone in the universe?

The chemicals were detected as the planet passed in front of its host star, allowing researchers to analyze starlight filtered through its atmosphere. The data revealed a sharp drop in light at wavelengths absorbed by DMS and DMDS—molecules previously found only in biological processes on Earth.

“The signal came through strong and clear,” Madhusudhan said. “It’s mind-boggling that this is possible.”

The chemical concentrations detected were thousands of times higher than those found on Earth. However, the results reached only a “three-sigma” statistical confidence level, meaning there’s still a 0.3% chance the findings were random.

Some scientists remain skeptical, noting that other non-biological processes could potentially produce the compounds. “Life is one of the options, but it’s one among many,” said Dr. Nora Hänni, a chemist at the University of Berne, who found DMS on a lifeless comet.

Others caution that conditions on K2-18 b are still poorly understood. While Madhusudhan’s team suggests the planet could host a vast ocean, other models propose it may be a gas giant or covered in magma.

Despite the uncertainty, the detection marks a major step forward in exoplanet research. “We’re trying to establish if the laws of biology are universal,” Madhusudhan said. “In astronomy, the question is never about going there.”

popular posts

As AI Grows, So Does Its Environmental Footprint

James Webb Telescope Detects Potential Signs of Life on Distant Planet

Sabin Launches U.S. Phase 2 Trial of Marburg Vaccine

Rwanda’s Mufti Praises Peace and Unity as Muslims Conclude Ramadan

Rwanda’s Health Insurance Contribution Set to Increase

Rwanda Launches Groundbreaking Research on Marburg Virus

Emirati Mother Beats Rare Cancer with Robotic Surgery

Youth Empowered with 170 Million Francs to Grow Their Agricultural Projects

Rwanda and Turkey Strengthen Ties with Landmark Agreements During Historic..

Ministry of Health to Include Community Health Workers in Muganga SACCO

Rwanda and China Partner on $50.7 Million Deal to Revolutionize Agriculture

Rwanda and Zimbabwe Expand Partnership to Boost Economic Development

Rwanda Aims to Eradicate Neglected Tropical Diseases by 2030

The African Union adopts ten-year strategy and action plan to transform Africa’s..

Rwanda and Qatar Sign Agreement to Boost Military Training and Cooperation

Rwanda Unveils Potential Oil Reserves in Lake Kivu, Paving the Way for..

Rwanda Kicks Off Campaign to Fight Stunting, Boost Maternal and Child..

President Kagame Hosts Oromia Leader for Talks on Rwanda-Ethiopia Relations

Rwanda Sees Surge in Electricity Exports and Imports

Rosatom has successfully progressed in manufacture of recycled fuel for fast neutron..

Rwanda Assures Public No New Flu Strain Detected Amid Seasonal Outbreak

Rwanda Sees Positive Progress in the Fight Against HIV

Rwanda Launches New Malaria Treatments as Cases Surge Across the Country

Rwanda Faces Rising Malaria Cases, Urges Action Against Mosquito Breeding

Rwanda’s Agricultural Sector Saw Growth in 2024, but Faced Challenges in Irish Potato..

Rwanda to Host Africa Headquarters of International Vaccine Institute

Rwanda Urges East African Ministers to Strengthen Regional Peace and..

Chorale de Kigali Promises a Joyful Christmas Celebration at 11th Annual Carols..

Rwanda’s Healthcare Workers Urged to Join the Fight Against Corruption

How Rwanda Overcame the Marburg Virus with Unity and Strength

Kigali Hosts EASF Chiefs’ Meeting, Marks 20 Years of Regional Peace Efforts

Rwanda and Germany Strengthen Partnership with New Climate Change and Environmental..

RURA Introduces New Bus Stops in Kigali for Holiday Season Travel

Rwanda’s Vision for Expanding Healthcare Workforce Supported by New WHO..

Rwanda’s Economy Shows Strong Growth of 8.1% in Q3 of 2024

EASF Marks 20 Years of Promoting Peace and Security at Key Kigali Summit

BNR Issues New Bonds to Boost National Development

Rwanda and Ethiopia Strengthen Police Partnership to Foster Peace and..

Prime Minister Dr. Ngirente Commemorates 30 Years of Post-Genocide Security and..

MTN Rwanda Partners with UNICEF to Protect Children Online

Rwanda’s Health Financing Model Quite Symbolic For Africa

New High-Tech Storage Facility to Boost Onion and Chili Farmers in Rwanda

Need for Rwanda Mental Health Nurses towards advancing their studies

Access to Sanitary pads still remains a challenge to get for Girls,..

NBR reduces policy rate as inflation remains within target

Uganda tackles yellow fever with new travel requirement

Google is building the first fiber optic cable connecting Africa and..

Africa Soft Power Summit Returns to Kigali

Rwanda, Mali sign agreements fostering developments

MPost rolls out electronic P.O. Box service in Rwanda

President Museveni Calls for More Foot and Mouth Vaccine Doses to Uganda

Rwanda’s districts show unprecedented improvement in public fund management for..

Successful pilot irradiation to produce samarium-153 medical isotope at Leningrad..

Rwanda to train 500 CAR police officers as countries ink new cooperation..

AU Commission Joins Rwanda to Advocate for Stronger Operationalization of the African..

BNR maintains repo rate at 7.5 percent

President Kagame holds talks with Salva Kiir of South Sudan

How Rwanda’s $4.2 billion MBRP is boosting economic recovery and industrial..

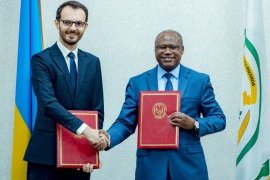

Rwanda, EU sign mining agreement to boost sustainable mining practices

Kenyan shilling firms, horticultural produce inflows help

Rwandan Horticulture Exporter Overcomes Hurdles to Build Thriving Produce..

EU signs critical raw materials deal with Rwanda

Kenya Government pledges continued collaboration with World Bank to enhance..

We have accomplished a lot together - Kagame commends relations between Rwanda and..

Polish President, Andrzej Duda begins three-day working visit to Rwanda

Landlocked Developing Countries Conference in Kigali to Address Development

Water For People commits to providing clean water to 1.5 million Rwandans

Uganda to extend e-cargo tracking system to South Sudan

RwandAir appoints AirlinePros as Singapore GSA

Rwanda steps up cancer screenings on World Cancer Day

RDB Chief optimistic towards Rwanda’s economic growth

African Union Peacekeepers Complete Second Phase of Drawdown from Somalia

Digital Microsavings Need Clear Pathway to Pump Life into African Economies

The Illuminating Journey of HWPL Peace Education Teacher Training: Power to Transform..

Rwanda, Belgium sign Rwf131 billion cooperation agreement

Kagame holds talks with Mamadi Doumbouya of Guinea

BK Removes Monthly Account Charges for all Retail Customers

Rwanda’s safari lodges are the ultimate in nature travel

President of Guinea, Gen Doumbouya visits Rwanda

National Cement Holdings successfully acquires CIMERWA factory

Three Years After AfCFTA Ratification: Should Africans Still Rely On..

Uganda in talks with UAE’s Alpha MBM to finance $4bn oil refinery project

Ugandan ride-hailing firm SafeBoda makes Kenya return

UNDP And African Leaders Launch Timbuktoo Initiative to Unleash Africa’s Startup..

BRD allocates Rwf15 billion to support bus acquisition for public transport in..

Rwanda eyes enhanced trade, investment ties with Pakistani

China, Uganda pledge to expand pragmatic cooperation

UoK appoints Prof. Felix Maringe as DVC for Institutional Development, Research and..

Infinite Business Solutions partners with Centrika to launch iKiosk payment solution..

Rwandan Tea Industry: A Catalyst for Economic Transformation

Tanzania Issues Alert Over Red Eyes Outbreak

Kagame, Rio Tinto CEO discuss partnerships and investment opportunities

WEF: President Kagame in Switzerland

Kenya seeks rapid resolution with Tanzania after announced flight ban

Saudi Arabia cuts domestic worker hiring fee from Uganda, Kenya and..

Can Africa save Christianity if the West gives up on faith?

IMF Report - Tanzania Least Indebted African Nation

I&M Bank to open 20 branches in Kenya this year

NAM summit kicks off in Uganda

Jasiri opens applications for 6th cohort of Talent Investor Program

University of Kigali Appoints Ogechi Adeola as DVC-Academic

10 African countries where fuel prices currently bite hardest

Tanzania Procures 3 Electric Trains for SGR

Govt greenlights strategic relocation for road infrastructure development

Scatec to divest interest in 8.5-MW solar farm in Rwanda

Applications for ICANN80 Fellowship Round Extended to December 29, 2023

RNP lauds public impact in crime prevention

Petrol price drops by Rwf183 per liter

Rapper Kendrik Lamar in Kigali

AfCFTA presents opportunity for Africa to pursue climate policies: UNECA

HWPL Unveiling Ceremony of Public Peace Art

Tanzania launches the national strategic plan to integrate health sector HIV, viral..

OX Delivers on track to make low-emission transport breakthrough

Uganda, Kenya Urged to Lift Visa Restrictions to Boost Tourism

’Africa’s oldest mother’ gives birth to twins aged 70 through IVF

Patriarch of Alexandria: Egypt is crown of Africa and Burundi is precious diamond of..

Kagame attends ’Sustainable Markets Initiative’ reception

HWPL and Timor-Leste Press Council Join Forces for Peace Journalism and..

Equity Group completes acquisition of Cogebanque Plc

Empowering children with music and dance in Rwanda

FIND and Rwanda Biomedical Centre sign agreement to support digitally enabled,..

BK Group PLC reports robust growth with Rwf55.1 billion profit in first nine months..

AfDB, RDB launch project to catalyze sustainable private sector growth in..

Uganda to borrow $150 mln from China’s Exim after World Bank halts funding

Kenya’s MPost relocates its headquarters to Rwanda

HWPL World Interfaith Prayer Conference 2023: Prayers for End of Wars

East African states seek to boost tourist arrivals

Rwanda, Burkina Faso Police Chiefs hold bilateral meeting in Kigali

Kagame holds talks with Cuban Vice President

Rwanda replaces female-dominated Police contingent in South Sudan

NIRDA explores bamboo as key raw material for sustainable construction

One in three women in world faces violence, Ugandan minister says

CIMERWA to become majority owned by new long-term investor committed to regional..

China-supported Luban workshop inaugurated at IPRC Musanze

MTN Rwanda in partnership with Rwanda TVET Board launches an Inter TVET..

Ecobank to offer 27 African nations cheaper loans

NALA Granted Licence for Cheaper and More Reliable International Payments in..

Somi Kakoma debuts as first Rwandan actor to appear on Broadway

More than 8000 graduate at University of Rwanda

Tanzania and Uganda assess feasibility of gas pipeline

MTN Rwanda in partnership with Rwanda Union of the Blind hosts annual Dinner in the..

Premier Ngirente highlights collaboration as key to tackling contemporary..

UAE and Ugandan leaders explore ways to strengthen bilateral cooperation

Parliament approves over Rwf148 billion loan for Kigali-Muhanga road rehabilitation..

Unlocking Rwanda’s Tourism Potential: A Journey Through Sports Partnerships

Tanzania Inks Deal to Export Natural Gas to Uganda

Kagame in Riyadh for the inaugural Saudi-African Summit

SFD inks $20m for Expansion towards Transmission and Distribution Water System in..

Bralirwa enhances local sourcing programs for sustainability

Rwandan chili farmers expect to explore Chinese market at import expo

Aleph Hospitality signs contract to manage its second hotel in Kigali

RwandAir on track to double fleet to better connect other routes

“Women for Bees” in Rwanda: Guerlain and UNESCO bring pioneering beekeeping program to..

Rwanda’s culture, heritage on show at expo

Gerayo Amahoro road safety campaign taken to taxi parks, highways

Rwanda generates US$241.8 million from mineral exports in third quarter of..

Trade between Rwanda, UAE Strengthened further

BasiGo Wins Best Mobility & Logistics Award At Global Startup Awards..

Rwanda to rotate two Formed Police Unit contingents in CAR and South..

Climate-smart cows could deliver 10-20x more milk in Tanzania

President Museveni defiant over removal from US trade pact

Over 80% of healthcare professionals in Rwanda live in rental accommodations

Call on Governments to incentivise production of sustainable aviation..

Rwanda announces visa-free travel for all Africans

Bruce Melodie and Shaggy team up for ’When She’s Around’

Kenya to lift visa requirements for all Africans: president

Uganda oil project reaches “major” milestone with “smart” pipeline delivery

Rwanda secures over Rwf64 billion in EU funding to support pre-primary..

South Sudan, Rwanda sign pact on police training

Rwanda, Polish bank sign Rwf29 billion financing agreement to support dairy..

Rwandan publisher launches card game to break mental health stigma

IGP Namuhoranye attends EAPCCO General Meeting in Burundi

Rwanda launches second wave of avocados freight shipment to Europe

RwandAir enhances its fleet with a seventh Boeing 737 aircraft

IMF warns Africa of economic vulnerabilities as China’s economy slows

Rand Merchant Bank (RMB) supports ambitious development outcomes in..

Zimbabwe Police Chief pays courtesy call on IGP Namuhoranye

Uganda Airlines Begins Direct Flight To Nigeria, Reduces Travel Time

Chinese tech company ZTE commits to accelerating digitization of Africa

I&M Bank Rwanda Plc introduces online account opening services

Choplife Gaming to Sponsor Producer Category at Trace Awards in Kigali

SPENN, MINICT join forces to drive financial inclusion in Rwanda

‘The Book of Life’: How one artist creates healing out of tragedy

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Names Kendra Gaither President of U.S.-Africa Business..

MTN Rwanda marks 25 years of pioneering mobile telecommunications

New envoys pledge deepened cooperation with Rwanda

BK first cross-listed firm on the Kenyan NSE-20 Share Index

Knitted knockers Rwanda by breast cancer survivors

SKOL Brewery Ltd empowers youth through scholarships

Airtel Africa boss highlights growing telco role in digital

Rwandan cassava seed inspection and certification capacity boosted by LAMP technology..

Rwanda, SoftBank claim 5G HAPS stratosphere first

Republic of Guinea opens embassy in Kigali

Airtel unveils Rwanda’s most affordable LTE smartphone with an exclusive..

Kenya seeks more Chinese loans at ’Belt and Road’ forum despite rising public..

Kenya’s First Locally Built Cargo Ship Enters Service on Lake Victoria

Norway closes embassy in Uganda

20 Buses arrive to ease public transport challenges in Kigali

Kagame hosts LG Corporation delegation to discuss business partnerships

Inaugural Africa Energy Expo set to take place in Kigali, Rwanda: Launching a new era..

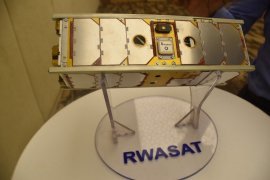

Chinese satellite to use Rwandan technology

Accelerating digital Africa at MWC Kigali 2023

180 Rwandan Police peacekeepers in CAR awarded UN medals for outstanding..

Global Experts in Rwanda to discuss way forward towards Space Industry

Kenya To Lose Trillions If LGBTQ Laws Are Implemented – Report

Central African Republic Gendarmerie Chief pays courtesy call on Inspector..

Africa: To Achieve Sustainable Growth in Africa, We Must Focus On Women

Putin sends congratulatory message to Museveni as Uganda celebrates Independence..

QFC and KIFC strengthen partnership for financial sector growth

University of Kigali champions value-creation through capacity-building

Ruto reveals details of planned meeting with Museveni

WTTC unveils theme, agenda for its 23rd Global Summit in Kigali

Rwanda, Brazil sign visa waiver deal

IGP Namuhoranye receives delegation from Qatar

WMA urges govts to move beyond political declarations to secure global health..

Expansion of Chinese-built hospital in Burera District completed

Sidra Medicine delegation from Qatar visits Rwanda

Security in Rwanda continues to improve - Minister Gasana

Uganda Airlines announces commencement of its India operations

Pope opens Vatican meeting amid tensions with conservatives

Heineken® Celebrates 150 Years of Good Times

Africa must intensify efforts to tackle socio-economic challenges: AU

Four questions with IFAD’s new Vice-President

Petrol price in Rwanda rises

African ministers call for new financing for continent’s development..

Rwanda, Mauritius sign MoU in the field of ICT

BRD floats first $25mn sustainability bond

UN council to vote on Kenya police deployment to Haiti

Rwanda, World Bank celebrate 60 years of strong partnership

Tanzania Taps Solar Energy to Boost Youth Employment

RNP honors retiring Police officers

Second phase of eKash launched

AWIM to host 7th annual conference on GBV in media

Rwanda accedes to United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Sale..

Rwanda Using a Community-Based Approach to Improve Maternal and Child..

South Sudan Parliament Changes National Currency Name

World Contraception Day 2023 - A Call to Liberate Women’s Bodies through Equitable..

Giant of Africa Festival 2023

Rwanda-bound fuel tanker bursts into flames in Kabale after accident

TradeFlow Capital Management enables scalable Carbon abatement in Rwanda

54 schools suspended over failure to meet quality education requirements

At Unstoppable Africa, Antonio Pedro makes strong push for industrialization and..

Kagame meets with Moussa Faki, Don Peebles and Barry Segal

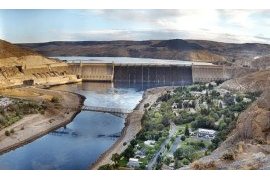

Kenya and Britain’s GBM sign deal for 1,000 MW dam construction

Minister Uwamariya visits Regional Centre of Excellence on GBV and Child..

Rio Tinto doubles down on lithium mining with Rwanda deal

Open Submissions for the New Cities Catapult

Sri Lankan conglomerate buys 90% stake in Unguka Bank

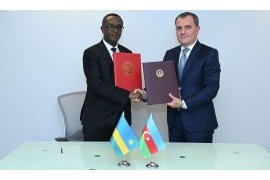

Rwanda, Azerbaijan MFAs sign MoU

IGP Namuhoranye urges youth volunteers to create impact in society

New strategies may reduce treatment failure in malaria by up to 81%

Africa Women Innovation and Entrepreneurship Forum (AWIEF) Announces Finalists for..

UN medals for Rwandan peacekeepers

Delegation from National Institute for Security Studies in Nigeria visits..

YouthConnekt Awards 2023 registration started with some categories added

President Kagame chairs Presidential Advisory Council

Google is bringing the Read Aloud feature of Microsoft Edge to Chrome

Congolese students in Tanzania, Kenya welcome visa waiver

President Ruto in Silicon Valley Charm Offensive

President Museveni, Al-Burhan discuss bilateral, regional issues

African Agro-Processors Call for Policies Conducive to Local Manufacturing

G-20 membership: What is in it for Africa?

Public–private partnerships could play role in ensuring water security

Davido, Asake, And Kizz Daniel Set To Perform At Trace Awards 2023

President Kagame in Cuba

Over 200 Police officers complete basic special forces course

Sub-Saharan wellbeing project takes another leap forward

Over 13,000 teachers recruited in 2022/2023 school year

President Kagame appoints Dr. Jimmy Gasore as Minister of Infrastructure

Harmonizing efforts against GBV and child abuse

Kagame receives message from his counterpart of Benin

Rwanda inks deal to host first demo Dual Fluid nuclear reactor

Brussels Airlines adds long-haul daily flights to Kigali

Borouge solutions supports energy sector in Rwanda

Coventry University strengthens ties in Africa through its Global Hub in..

Private security companies urged on service delivery

President Kagame urges youth to Utilize their potential

80 Rwandan students get Chinese scholarships to pursue studies in China

MTN Rwanda, Mobile Money Rwanda partner with City of Kigali to secure motorcyclist..

I&M Bank Rwanda registers Rwf7.2 profit before tax in first half of..

Ministry of Public Investments and Privatisation absorbed to Minecofin

Somalia could join EAC by December - secretariat

Titles from Rwanda and Kazakhstan awarded PEN Translates awards for first..

Somalia bans TikTok and Telegram to curb "terrorist" propaganda

President Museveni Says World Bank Arrogant for Halting New Funding

BNR increases lending rate to 7.5 percent

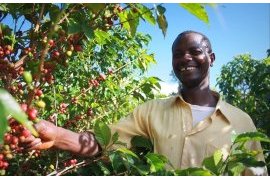

Profiting from Rwanda’s avocado and chilli export potential

Scientists discover why some Africans have lower HIV viral loads

South Korea FM visits Rwanda, seeks future-oriented cooperation

Rwanda generates over Rwf290 billion from tourism in first half of 2023

Rwandan peacekeepers under UNMISS decorated with medals

Google introduces new privacy tool updates to protect user safety online

Tanzania Offers Ugandan Shippers 30-Days Free Storage Period

Rwanda’s inflation rises by 11.9 percent

Rwanda, Jordan ink deal to waive visa requirements on regular passports

Police out to enforce lighting in automobiles

Uganda, Kenya hope to raise $6bn to restart Mombasa railway

Study Shows High Patient Satisfaction with AI Eye Screenings

World Bank suspends lending to Uganda over new anti-LGBTQ law

Interview with Charles Butera, author of the book "Temoins a Nu” (“Bare Witness”), a..

The Peace Wall-painting Project, Jointly Organized by the International Peace..

RDF, US Army carryout medical outreach in Bugesera district

Rwanda, Madagascar sign private sector agreement to foster cooperation

Ambassador John Mirenge presents his credentials copy

Amb. AlQahtani shares UAE’s journey in responsible use of Artificial Intelligence with..

MTN Rwanda’s half-year results reveal remarkable growth in home connectivity

Rwanda & Barbados Sign Tourism MOU

UN official calls for new approaches to reap benefits of AfCFTA

IGP Namuhoranye attends Botswana Police awards ceremony

Air Connectivity to Strengthen Barbados & Rwanda Ties

Pak-Africa Business Forum discusses trade with Rwanda

President Kagame inaugurates Chinese-invested cement factory in Muhanga

Gerayo Amahoro campaign shifts to cyclists

Agri-food sector stakeholders in Rwanda discuss best practices to handle food..

Goodwell invests in SOUK Farms to scale sustainable agricultural production across..

Africa Mobile Networks inks deal with Starlink to connect millions of people in..

Ikirenga Art and Culture announce second edition of Culture Tourism..

Uganda’s Government halves public sector internet data costs

Ambassador Marara meets Minister of Interior from Qatar

Experts call for heightened efforts to address cyber security

Bralirwa Plc reports 2023 First Half Year Results

Kenya suspends local activities of crypto project Worldcoin

Tanzania: Ghana Launches Afcta Trade Expedition to Tanzania

Rwanda seeks contractor to digitize civil registration archiving system

United Nations (UN) Women Executive Director visits Rwanda

UK-based company seal earn-in deal for Rwanda lithium project

Former Minister of Agriculture, Dr. Mukeshimana appointed IFAD vice..

Rwanda prepares for Exchange of Information On Request Peer Review

Rwanda Progresses in gender equality

Security reassured as Rwanda International Trade Fair starts

Pope Francis Urges Russia To Return To Ukraine Grain Deal

Airtel Rwanda pledges to join RNP to extend Gerayo Amahoro Campaign

Kenya opens sub-Saharan Africa’s first stem cell research lab

Equity Group acquires Cogebanque Plc

Uganda to host Africa Coffee Summit next month

MTN Rwanda starts Celebrates 25 years with great extravaganzas lined-up

Uganda signs agreement with Russia on NPP construction

East African Power to build 266 MW of solar in DR Congo

Burundi Upbeat With Tpa Resolve to Simplify Cargo Transportation

Uganda: MTN launches first 5G network, UCC Clears Airtel

Rwanda elected to UNWTO Executive Council

The role of leadership in supporting mental health and wellbeing in the..

Kenyan electric bus manufacturer BasiGo expanding to Rwanda

Kasha has raised $21M series B led by Knife Capital to expand in Africa

Bugesera International Airport projected to make African aviation take..

Mira Aerospace completes HAPS test flight in Rwanda

Chinese-sponsored technology contest for African youth launched in Kenya

Women’s Participation Is Shaping the Future of Travel & Tourism Sector

The Chilli Mash Co launches £100k crowd round for sustainable chilli farm in..

Why Regional Energy Hub Tag Beckons for Tanzania

EAC currencies gain against dominant Kenyan shilling

Twitter to be renamed X, ditch bird logo

RwandAir set to launch daily nonstop London flights

Nearly 100 Babies Saved in Three Months as Caesarean Sections Made Available in a..

RwandAir signs cargo handling contract with Worldwide Flight Services

Rwanda, Burundi commit to expanding bilateral ties

RwandAir celebrates ‘year of success’ with its first Awards Night in..

The African Trade and Investment Development Insurance (ATIDI) Posts Resilient..

UAE signs $1.9 bln mining deal with Congo

UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador Vanessa Nakate takes a stand for Adolescent girls during..

Zimbabwe agrees to sell maize to Rwanda

Much more remains to be done to tackle bias attitudes about gender -..

Women Deliver 2023: Leaders discuss gender equality challenges and way..

Bboxx, MTN Rwanda sign partnership to increase smartphone access in..

WHO Addresses Violence Against Women As a Gender Equality and Health..

Rwanda, Poland sign Tax Solidarity MoU to Enhance Efficiency

Rwanda plans to set up Lithium refinery

Rwanda presents progress on SDGs under VNR 2023 in New York

Rwanda, Singapore Police forces hold bilateral meeting in Kigali

New bacterial strain linked to Hydrocephalus in Ugandan infants

Rwandan farming communities kick start cold-chain in continent

President Novák Visits School and Hospital in Rwanda

Rwanda to open diplomatic mission in Hungary

Primary leaving exams Starts countrywide

FDA impressed by Zimbabwe’s medicines regulatory systems

Religious leaders in Kenya urge Ruto to repeal a new tax law as protests..

ADB Group commits $101 million to sustainable water and sanitation reforms for..

President Kagame receives Prime Minister of São Tomé and Príncipe

Over 500 Police Cadet Officers commissioned

Youth from diaspora briefed on Rwanda’s Liberation Struggle

Amb. Kimonyo presents credentials to represent Rwanda in Pakistani

EGF launches competition to boost export-oriented businesses in Rwanda

MTN Rwanda donates Rwf100 million for construction of maternity ward in the Bweyeye..

Zimbabwe agrees to sell maize to Rwanda

Uganda imposes tax on foreign digital companies’ income

Rwanda Food and Drug Authority delegation in Zimbabwe

SDF Finances Electricity Project in Rwanda with USD20 Million

Rwandan youth living abroad visit RNP

DNA paternity test services in Rwanda increased nearly four-fold in five..

Aegis partners international conference on peace education in an era of..

Why Equity paid Rwf 54.68 billion for Cogebanque

Rwanda looks to work with Caribbean countries for vaccine production

Rwanda in Africa’s top 3 in global skills ranking

Twitter vs. Threads: The Musk-Zuck Cage Match That’s Actually Happening

Prime Minister calls for strengthened partnerships of Africa

Ethiopia could be the engine of economic growth in sub-Saharan Africa

OPEC Fund and partners finance new power transmission line in Tanzania

WOMEN DELIVER CONFERENCE TO BE HELD NEXT WEEK IN KIGALI

Feeding Rwanda: how small-scale irrigation can help farmers to change the..

18 million doses of first-ever malaria vaccine allocated to 12 African countries for..

Kenya economic growth beats estimates as Agriculture picks up

Defence Attachés to Rwanda briefed on RDF operations, internal and regional security..

We mustn’t lose momentum in war against neglected tropical diseases

Rwanda, Uganda open new border post

US measure would ban products containing mineral mined with child labor in..

First double-deck coaches arrive in Tanzania for Standard Gauge Railway

Pope Francis condemns Swedish authorities’ decision to allow Quran burning

Payday and SpaceX firm Starlink link up to bump financial inclusion in..

Rwanda seeks sustainable packaging investors

I&M Bank Rwanda Awarded as Best Bank in 2023

BK Urumuri Initiative competition open to twenty five businesses

Uganda’s Tilenga project expected to commence oil production in 2025

President Kagame in Seychelles for state visit with key agreements signed

Tanzania warns against foreign currency pricing

RWANDAIR STARTS DIRECT FLIGHTS TO PARIS

Rwanda gears up to unveil conservation agriculture mastery at Doha Expo

Minister Marizamunda stresses need for collaboration to maintain regional..

ECA Report: No African country on track with 2030 SDG goals

44 Police officers complete Individual Police Officers’ course

Can Fintech fast-forward development in Africa?

123 Police officers complete basic criminal investigation course

Rwanda Post Office unveils RwandaMart to connect traders to local and international..

Fintech key to accelerating Africa’s socio-economic transformation: delegates

East Africa bloc, FAO warn of Rift Valley Fever outbreak in eastern..

Chipper Cash Launches in Rwanda at Financial Inclusion Conference in..

Ansys Expands Presence to Africa with New Office in Rwanda

President Kagame to be guest of honour at Seychelles’ National Day parade

Rwanda signs agreement for introduction of electric buses in Kigali

Kenya Airways Unveils Brand New Exciting Loyalty Program to Reward Travelers

IATA launches programme to improve Aviation Safety in Africa

Africa’s potential lies in its social entrepreneurs — here’s how we nurture..

President Kagame hosts state banquet in honour of Zambian counterpart, Hakainde..

UNHCR celebrates refugee inclusion in Rwanda

MTN Rwanda launches of eSIM technology

Minister Uwamariya urges students to shun drunkenness, drug abuse

Poland, Rwanda FMs discuss economic cooperation

Tanzania path to a strong digital backbone

EU, Kenya Sign Trade Pact Seen as Model for East African States

Rwanda’s economy grows by 9.02%

Africa Needs More Women in Fintech

Afrexim bank unveils Afrexinsurance, “latest African financial weapon”

Rwanda’s head of diplomacy to visit Poland

Airtel Rwanda launches e-SIM

UAE Ambassador to Rwanda inspires ESSI students on path of tolerance

Tanzania sees spending rising 7% in 2023/24 budget

Kenya: Lawmakers pass budget, biggest in country’s history

Mr Eazi’s multi-million estate project in Rwanda leaves Nigerians stunned

National budget increases to Rwf5,030.1 billion

Africa needs grain imports, key states say ahead of Putin talks

Visa unveils new initiative to support fintech start-ups in Africa

Ugandan anti-LGBTQ law deepens Anglican Church rift on gay rights

Experts advocate for development of robust basic sciences in Africa

Equity Bank buys 92% stake in Cogebanque

Police key to reducing youth crime, says Minister Utumatwishima

Streamlining tax payments: How Bank of Kigali’s digital channels redefine..

Rwanda registered 45.7 percent increase in FDIs in 2021

Young people are abandoning news websites - new research reveals scale of challenge..

Kenya starvation cult death toll exceeds 300 after 19 more bodies found

Rwanda, Russia commit to reinforcing existing diplomatic ties

Eritrea rejoins East African bloc 16 years after exit

Mass driving tests kick off

UNMISS Chief of Police Operations visits Rwandan peacekeepers

EU-Rwanda Business Forum to set stage for stronger trade and investment..

RUBAVU: Police thwarts attempt to traffic narcotics in potato sack

Pope Francis recovery going well but will skip Sunday blessing

Rwanda’s inflation increases by 14.1 percent in May 2023

Kagame meets with delegation of Volkswagen Group Executives

Uganda: President Museveni reports economic growth, eyes infrastructure

Anti-drugs campaign launched in Nyarugenge

President Kagame, Touadera discuss bilateral cooperation

AEE Rwanda to support youth involved in horticulture

ADB-funded project boosts universal access to water in Rwanda

Rwanda leaps forward in journey to build innovation ecosystem

Electric mobility startup Ampersand achieves major milestone with 1,000..

Africa has technology and innovation to achieve zero hunger- Dr. Adesina

Air Tanzania expands cargo services with delivery of Boeing 767 Freighter

DIGP Ujeneza receives delegation from Guinea

Commonwealth Trade Ministers meet to foster cooperation

Gerayo Amahoro awareness in churches

Police Handball Club wins Genocide Memorial Cup

KCB Group increases shares in BPR

President Kagame in Turkey for third term swearing of Tayyip Erdoğan

UAE President awards Medal of Independence to Ambassador Hategeka

RNP takes Gerayo Amahoro campaign in public institutions

How big tech and AI can make early warning systems more effective

Public perspective on Gerayo Amahoro road safety campaign

Rwanda and Latvia undertake to promote economic cooperation

MTN Rwanda launches Y’ello Next Level in Gatsibo District

Kigali: HWPL extends Peace education to APADE during annual commemoration of world..

TIME to Bring the TIME100 Summit in Kigali

CIArb launches Rwanda branch

HWPL Peace Educator Training Program in South Sudan, Rwanda, Burundi

TechAffinity Rwanda to Showcase Services at GITEX Africa 2023

Bank of Kigali first-quarter profit up 14.5 percent to Rwfs17.88 billion

President Kagame Joins World Leaders for President-elect Tinubu’s Swearing-In..

New integrated payment platform to be launched in Africa

Rwanda National Police enhances peacekeeping capacity through UNITAR..

Mobile Money Rwanda Ltd launches MoKash ‘TubiriMo’ campaign in partnership with..

First-ever kidney transplant successfully performed in Rwanda

Ukraine to open embassy in Rwanda

I&M Bank Rwanda posts 12% profit increase in first quarter of 2023

Rwanda takes Major leap towards an air Cargo Hub

Police extends Gerayo Amahoro campaign to community gatherings

Qatar one of the most important partners of Rwanda: Kagame

Bugesera International Airport construction expected to hit 70 percent by end of this..

Police takes road safety campaign in schools

President Kagame attends Qatar Economic Forum

AfDB shares its projects in East Africa region

Fintech firm dLocal receives regulatory licenses to operate in Rwanda and..

Rwandan Catechists on a pilgrimage journey in Uganda

Putting Adolescent and Youth SRHR at front and center in Rwanda

Media plays key role in road safety, DIGP Sano

Rwanda seeks to secure business partnerships with China at 6th CIIE

Rwandan Police peacekeepers recognized in CAR

Miss Innovation 2022 gets support from VAF for her project

Zimbabwe commits to implementing key reforms to resolve debt burden, end 21 years of..

EU-Twinning project Kicks off to strengthen Rwanda FDA in its regulatory..

Rwandan women entrepreneurs showcasing diversity in arts and culture

Rwanda rotates Formed Police Unit in South Sudan

Progress in implementation of agreements aimed at strengthening relationships between..

RwandAir, Qatar Airways launch African Cargo Hub for enhanced services at..

MTN Rwandacell gains strong top line performance in first quarter of..

Rubavu District: Bralirwa Plc donates Rwf 230 million for completion of a TVET..

Rwanda’s tourism revenue up 171 percent in 2022

STOP SIDA: On-going RBC campaign against HIV/AIDS through positive eyes..

RNP starts issuing digitalized Provisional driving license

Africa Press Conference of Shincheonji Church attended by journalists from 55 African..

The disturbing persistence of child defilement and teenager’s pregnacies cases – RIB..

African Water Facility has raised €1.4 billion and funded 117 projects in 52 African..

NYABIHU: Culture and negative masculinities, hindrances to women rights and values in..

Energy: Gasmeth Energy to invest $400m in Kivu methane extraction

RwandAir to Launch Kigali-Paris nonstop Flights

Rwanda using innovation to improve grain quality with support of IFC

Bralirwa Plc reports impressive Rwf22.5 billion profit in year 2022

BRD and Q-Lana partner to digitize Credit Management Process

Macye macye’program makes remarkable impact

Rwanda Well represented at tourism exhibition in Germany

Rwanda’s Cultural Heritage: An interview with Bigirinka G Innocent; an Entrepreneur in..

BPR Bank Rwanda Launches its new brand tag

Vaccination Boosts Efforts to Curb Rift Valley Fever in Rwanda

Rwanda is to Host The Agriculture Business Summit – AGRF 2o22 Summit

Democratic Republic of Congo: revival of livestock farming on several farms in North..

African Development Bank chief visits Dangote oil refinery and petrochemical..